A long vertical pipe sits against white-painted brickwork in the corner of a cramped storeroom. Two men wearing orange boiler suits and gloves crouch at its base. One uses a scraper to remove lumps of what looks like wet papier-mâché from the outside of the pipe, into a red bag held by the other. Both men are breathing through facemasks, their air sucked from outside the isolation unit: a short, makeshift corridor constructed from black plastic panels and transparent polythene sheeting. An extractor fan hums relentlessly.

It might look like a scene from a horror movie in which scientists fight to contain a virus, but the truth is more banal – though no less deadly. The two men are removing asbestos insulation from a heating pipe in a west London hospital. Ordinarily there would be bright yellow tape with the words “WARNING asbestos” on it, the site supervisor tells me. But this is an especially sensitive job. The neighbouring ward’s beds are filled by patients with acute respiratory conditions, and the hospital’s management decided that advertising the true nature of the work might cause alarm.

Thirteen people a day in the UK die from exposure to asbestos – more than double the number that die on the roads. In the USA, asbestos will be responsible for around 10,000 deaths this year, meaning it kills close to as many people as gun crime or skin cancer.

Health fears associated with asbestos were first raised at the end of the 19th century. Asbestosis, an inflammatory condition affecting the lungs that causes shortness of breath, coughing and other lung damage, was described in medical literature in the 1920s. By the mid-1950s, when the first epidemiological study of asbestos-related lung cancer was published, the link to fatal disease was well established.

Yet in 2012, rather than falling, worldwide asbestos production increased and international exports surged by 20 per cent. A full ban did not come into force in the UK until 1999, and the European Union’s deadline for member states to end its use was just nine years ago. Today, asbestos is still used in large quantities in many parts of Asia, eastern Europe and South America, while even in the USA and Canada, controlled use is allowed.

The remarkable endurance of this magic mineral turned deadly dust is a complex tale. One of scientific deception and betrayal, greed, political collusion, the power of propaganda, and, above all, the willingness of some executives to knowingly subject hundreds of thousands of vulnerable people around the world to severe illness and even death in the pursuit of profit.

Magic minerals

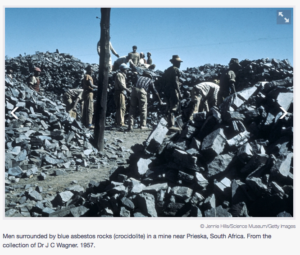

Asbestos is a generic term used to describe six naturally occurring minerals made up of thin fibrous crystals. Chrysotile, or white asbestos, is the only form still in use, and accounts for 95 per cent of the asbestos mined and used by humans historically. Its curly fibres make it more flexible than a family of five other forms known as the amphiboles – amosite (brown asbestos), crocidolite (blue asbestos), anthophyllite, tremolite and actinolite – which all consist of needle-like fibres.

The characteristics of asbestos – strong, lightweight and heat-resistant – and the fact it could be split into fibres, mixed with other materials and easily shaped meant that use of the mineral soon caught on. Large-scale mining began in the second half of the 19th century in the USA, Italy and Canada, and during the 20th century it was incorporated into a huge variety of products, especially building materials such as concrete, pipes, cement, bricks, tiles and insulation for buildings and ships. It was also used in car parts, protective clothing, mattresses and even cigarette filters. The industry significantly expanded during both World Wars.

You may not have to look hard to find asbestos where you live or work. Many buildings still have asbestos-based components, including pipe insulation, decorative coatings, ceiling boards, fireproofing panels, window in-fill panels and cold water tanks.

Research into precisely how asbestos causes mesothelioma and other forms of lung cancer is ongoing. The fibres are so small that most can only be seen under a microscope. Billions can be inhaled in a single day with no immediate effect, but longer-term the consequences can be deadly.

The fibres can become lodged in the lining of organs such as the lungs, causing damage that interrupts the normal cell cycle, leading to uncontrollable cell division and tumour growth. Asbestos is also linked to changes in the membranes surrounding the lungs – the pleura – including pleural thickening, the formation of scar tissue (plaques), and abnormal collections of fluid (pleural effusion).

“There is absolutely no doubt that all kinds [of asbestos] can give rise to asbestosis, lung cancer and mesothelioma,” says Paul Cullinan, Professor of Occupational and Environmental Respiratory Disease at the National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London. “It’s probably the case that white asbestos is less toxic in respect to mesothelioma than the amphiboles. The industry tries to argue that you can take precautions so that white asbestos can be used safely, but in practice, in the real world, that is not what is going to happen.”

This is the firm scientific consensus. But not everyone agrees.

Read the rest of the article at: https://mosaicscience.com/story/killer-dust

Source: Killer dust | Mosaic